On Slipping Across: Reading, Friendship, Otherness (from the introduction to Gus Blaisdell Collected UNM Press 2013)

by David B. Morris

Camerado! This is no book;

Who touches this, touches a man;

(Is it night? Are we here alone?)

It is I you hold, and who holds you;

I spring from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.

—Walt Whitman, “So Long!”1

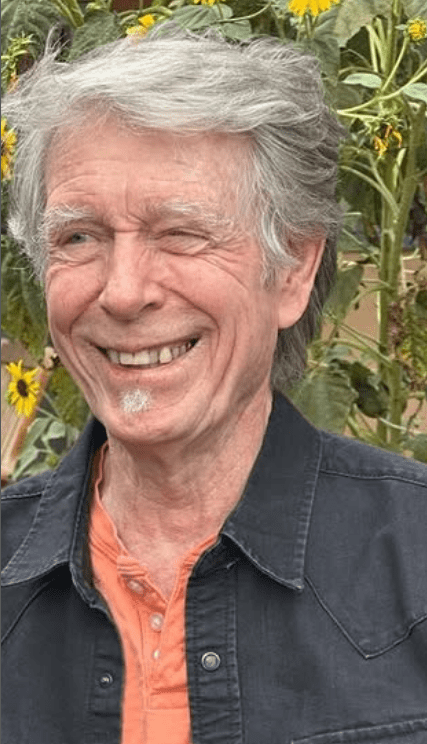

There are worse fates for a writer than finding your book–ink still fresh from yesterday’s megastore signing event–in the remainder bin. That’s where Gus found me. As owner of an independent bookstore where he selected and very often read the books he sold, he knew that megastores order by corporate logarithm and sell in bulk, so their remainder bins are a treasure trove for books destined to fail the test of mass sales. I like to think my good fortune lay in having built a final chapter around ideas of everydayness borrowed from philosopher Stanley Cavell. Over our lunches, I learned that Gus talked weekly or daily by phone with the eminent Harvard thinker, who shared his passions for film, music, and complex mental explorations, minus the bombast. Luckily I hadn’t built my chapter around the obscure academic theorists whom Gus hated for their amped-up profundities and treated to colorful obscene denunciation.

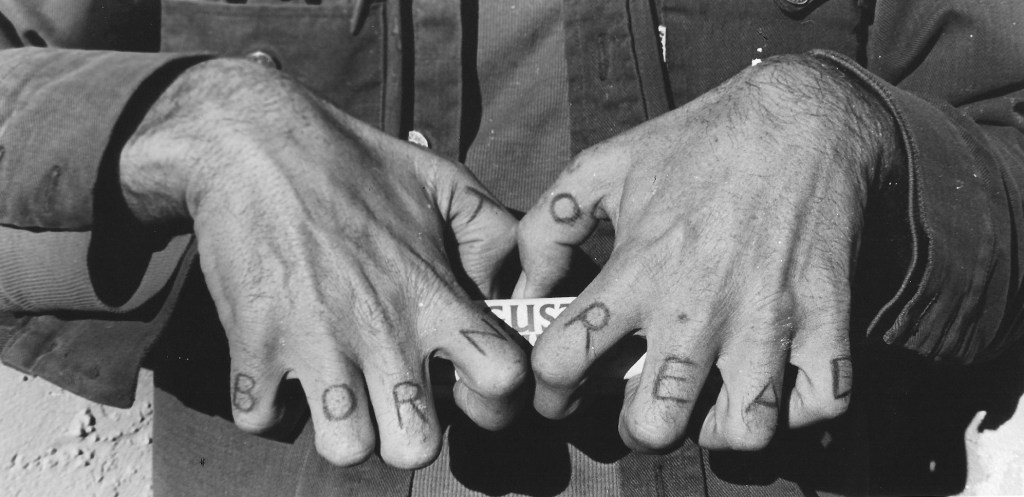

An unknown caller asks if I’m the guy who wrote the book in the remainder bin. Swallowing my pride, I offer a noncommittal yes, and the caller says we should meet for lunch. So begins a deep friendship of contraries. When I last saw him Gus was teaching a film course he called “Teen Rebels.” Was it veiled indelicate autobiography? On his fingers, between the knuckle and first joint, I could just make out the faded tattoo letters l-o-v-e and h-a-t-e, one letter per finger, one word per hand. Unlike the commercial barbwire designs on biceps at my local gym, these ancient high school tattoos–self-inscribed with a sharp instrument and ballpoint pen–stood out both as verbal artifacts and as silent provocation, fists as texts, which hand do you want. With Gus you pretty much knew where you stood. Also, bodies mattered.

I never got to tell him that the poet’s one-long/two-short dactylic rhythm takes its name from the Greek word for finger (dactyl)–as fingers contain three bones, one long and two short. Gus liked a poetry of bodies. He was a connoisseur of bodies. He savored their local properties and earthy flavors like a devotee of fine wine. In paintings, on the big screen, in the classroom, bodies with their erotic charge fascinated him, and he could fall in love instantly with a crooked smile or well-filled denims. William Blake belonged in Gus’s personal pantheon, and it seems fitting that certain bedrock Blaisdell values would find expression in Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell through the voice of the devil: “Man has no Body distinct from his Soul–for that called Body is a portion of the Soul discerned by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.”

Zen Buddhism offers another corrective to what Blake’s devil describes as the errors caused by all bibles and sacred codes. In this spirit, I suppose, Gus put me onto the fifteenth-century Japanese Zen master Ikkyū who wrote raunchy haikus about his sexual affair at age seventy-seven with a young blind temple attendant:

don’t hesitate to get laid

that’s wisdom

sitting around chanting

what crap2

We both loved the eros-inflected anti-cubist nudes of Amedeo Modigliani that Gus in a poem accurately described as women with “apricot thighs” and “offset twats.” The two dense, primal inscriptions on his hands–nouns? verbs? imperatives?–weren’t exactly pre-concrete one-word living poems carved into the flesh, fading as the flesh aged, but they sure weren’t decorations, and their position “in” the body (not on top of it) is serious stuff.

I also regret that I never got to ask him about Marlon Brando’s star-making turn in The Wild One (1951). Brando as leader of the pack is perhaps too post-adolescent to make the teen rebel course, although teens idolized him. I saw Gus, however, less as Brando than as Brando’s whacked-out rival gang leader, played by Lee Marvin. In contrast to Brando’s leathered-up, chip-on-the-shoulder, silent machismo, Marvin gabs incessantly. He is antihero to Brando’s antihero, twice removed from respectability, who would rather fight than win, and afterwards (sweat-stained and bloody) sits down with the winner for a beer. A trace of berserk androgyny in Marvin’s performance, like a body absent several crucial bones, exposes the oddly effete and rigid, passive-aggressive petulance that threatens to destabilize both Brando’s alpha-male vertical hierarchy and the entire fifties reverse morality play it underwrites (free-spirited bikers vs. repressed townspeople). Brando is still in uniform–biker uniform–right up to the shiny visor on his cap. So Gus slipped the mold, shape-shifting in my imagination from Brando to the grizzled, inscrutable, anarchic, crypto-androgyne and hedonist mutineer, Lee Marvin.

Lunch was our symposium, first at an eatery he chose so deep in the Latino zone that I feared for my life, later (perhaps as a concession) at a surprisingly upscale Nob Hill bistro where everyone knew him from manager to dishwashers, and occasionally in winter (as the snow fell) over a hot bowl of chili-with-polenta at the ambience-free Frontier Restaurant. We engineered a friendship that–with one exception–never saw the interior of a house. It was a nondomestic closeness that invoked, but rarely intersected with, our personal lives beyond the lunch table, as if we engaged in a deliberate mutual anthropology of thin description. We both shared a sense of how much the absent thickness mattered. The real presence in our conversations, however, was thought. Not just ideas or opinions. We talked about essays we were writing. We traded favorite writers and artists like kids swapping baseball cards. Those two faded words inked onto his hands governed his instinctual and considered response to the world, where he did not look for middle ground (as I did). Noncommittal relativist postmodern bureaucratic sellouts incensed him. When I knew Gus in the last years of his life, but I suspect this fact never changed, passion and thought always circled back to an interconnected triad of absolutes: family, friends, and art.

My vision of Gus, when Lee Marvin isn’t messing with my head, blends with Ezra Pound. Ego-driven, irascible, impossible, terms I would not apply to Gus although sometimes they brush close, Pound described his conversations with the young poets who visited him in Rapallo as their Ez-uversity. Our lunches were my Gus-uversity. I always learned so much more than I could possibly impart that I wondered why Gus put up with such an inherently losing transaction. Maybe he sensed an archaic teen rebel buried beneath my credentialed exterior, or more likely he just didn’t count costs. I learned that half the literary figures who interested me turned out to be his friends. During our lunch one time he was trying to decide if he would fly to California for Ken Kesey’s funeral. They’d known each other since the days of dropping acid at Stanford. The poet I called Robert Creeley was Bob. Once I mentioned a contemporary artist who amazed me away with his installations exploring various aspects of light. Did he know the work of James Turrell? Turns out they go back together to the sixties in Santa Monica. You mean Jim?

Samuel Johnson, according to a guy I knew, actually liked it when Boswell asked him those incessant moron questions such as why do foxes have a bushy tail. Non-thought can be a useful catalyst for thought. Young Boswell, inventor of the identity crisis, would leave himself self-fashioning notes that said, for example, “Be Mr. Addison” or “Be Macheath” (incompatible states of being, incidentally). Our lunchtime tandem somehow worked, but often I drove home wanting to leave myself little notes saying, “Be Gus.” His literary instincts were as right as Johnson’s–hardly infallible but never conventional, faint-hearted, or indecisive. It is Gus who awarded a fellowship to then unknown Leslie Marmon Silko. One day I saw a first-edition Ceremony for sale and warned him that somebody must have stolen it, because the fly leaf contained Silko’s handwritten thanks to Gus Blaisdell. No, it wasn’t stolen, he said. He didn’t believe in keeping a book just because it was valuable. An ideal time, in fact, to send it back into circulation. Not a book, however, that I would have let slip away.

“Slipping Across” is the title of a late essay Gus wrote, less an essay than an associative meditation or meditative slipping, and the two-word title repays consideration. It names a form of motion generally associated with bad results. You slip and fall. A stock price slips. A slip of the tongue exposes you. Orthodox people work hard to resist slippage, which is probably why it attracted Gus from the moment he found a fragment in The Greek Anthology that purported to be words spoken by Socrates: the philosopher’s erotic recollection of a kiss in which the soul (“poor thing”) hoped to slip across from lover to beloved. It is a paradoxical moment, joining transcendent hope and preordained failure: the soul is misguided, Socrates implies, because it doesn’t understand that you can’t just slip across. The moment for Gus prefigures the mysterious, tentative, possible/impossible union of writer and reader. As writer, Gus understood and accepted difficulties inherent in writing. “Yet the reader,” he says correctly, “is a problem.”

What is problematic concerns precisely the potential for slipping across–an ecstatic union and inevitable disunion–basic to an act of reading, which Gus characterizes as more passionate and more fleeting in its erotic intoxication than the memory of a soul kiss (did it happen?) between the middle-aged, snub-nosed, barefoot philosopher-satyr, Socrates, and the celebrated poet, Agathon, host of the famous drinking party devoted to the subject of love that Plato immortalized in The Symposium. Leave it to Gus to invent an erotics of reading. (As inventor, Gus cheerfully ignores and subsumes both the lustiness of Walt Whitman’s writer, reaching out to embrace the reader, and the prurience of Roland Barthes’s receptive reader, desiring his/her own ravishment.)

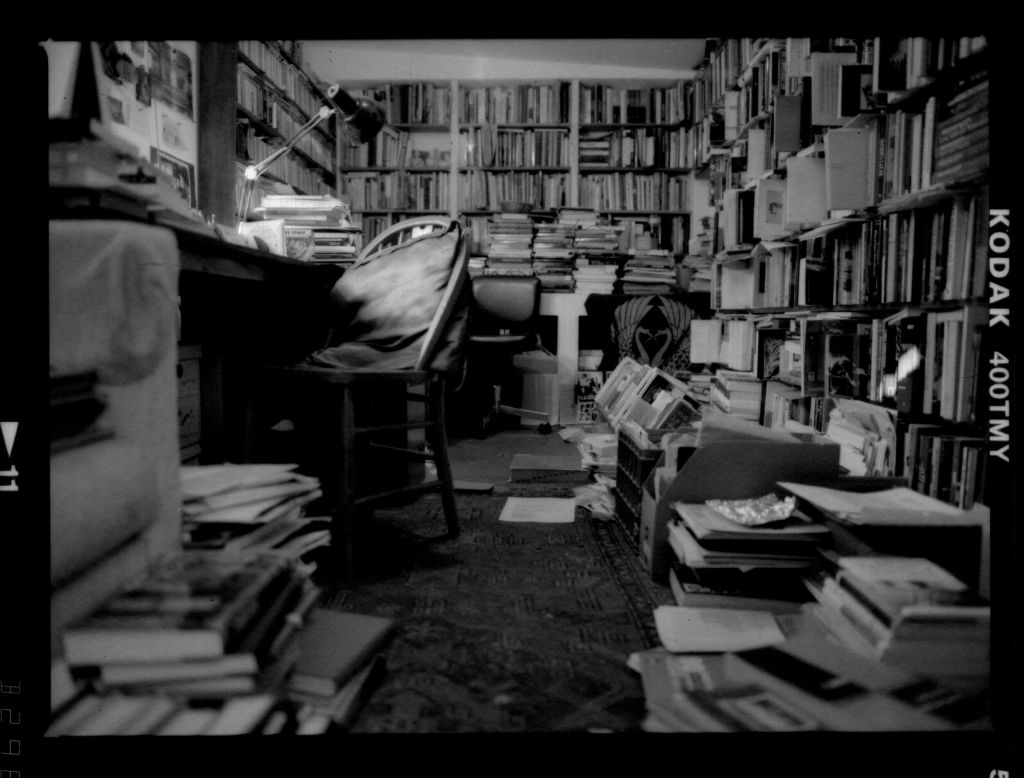

Over lunch during its lengthy genesis we often talked about the ideas that surface in “Slipping Across,” although I didn’t then know its title or grasp its focus on reading. Oddly, the image that occupied our talk then holds a less prominent position in the finished essay–Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial–which receives a scant paragraph plus. It is worth pausing over that sculptural monument here because it stands as a central metaphor for the complications of a slipping-across reading. It compresses in an image, appropriately mute, both the impossibility of reading and reading as impossible.

It is the cast-concrete replica of a personal library, such as Nazis confiscated from Vienna’s murdered, doomed, or departed Jews (the people of the Book). But it is a library suppressed, stripped to its inner core, negated and turned to stone. A cast made directly from a book-lined room, the monument is a library’s death mask. The books (reversed on their shelves so that the spines face inward) are unreadable, the serried pages facing the viewer are lodged within the solidified cube of the library’s interior and cannot be opened.

As Gus notes, an inscription on the Holocaust Memorial reads: “In commemoration of the more than 65,000 Austrian Jews who were killed by the Nazis between 1938 and 1945.” Around the base are inscribed in readerly script the names of the death camps to which Nazis sent the dispossessed Jews, including, in alphabetical order, Auschwitz, Belzec, Bergen-Belsen, Brcko, Buchenwald, Chelmno. . . .

Human mortality is not Whiteread’s subject–or at least not in Gus’s slipping-across interpretation–but rather catastrophic loss and, as its entailment, the impasse and obstruction that make reading impossible. Impossible in two senses. The Holocaust Memorial remembers the impossibility of reading under totalitarian regimes, where book burners seek to immobilize the autonomous movement that makes reading always potentially subversive, like a nighttime raid slipping across enemy lines. Totalitarian regimes attempt to stifle reading in order to solidify their own deathly power, much as the marmoreal cast stone of the Holocaust Memorial fossilizes (in rigor mortis pallor) all the rich colors and complications of a living library. As good, almost, to kill a man as kill a good book, wrote John Milton in his pro-dissent, anti-monarchial tract against censorship. (In its complexities, however, Areopagitica says it’s necessary to restrict Catholic writings, as a counter to the perceived totalitarian hold of the papacy.) Reading, through its slippage and its intimate link with eros, supplies an antidote to totalitarianism’s monolithic rigidity, operating as an implicit act of defiance, resistance, and insubordination.

The implicit political dimensions of reading, however, invoke a deeper conflict native to the desired union between reader and writer. The impossibility of reading in this second sense, as reflected in Whiteread’s Memorial, recognizes the forlorn failures of eros. The readerly desire for communion with writers, a genuine moment of slipping across, resembles the slippery goal of erotic experience: the lineaments of gratified desire, in the phrase of William Blake that haunted Gus. An initial sense of lack, an inherent absence and elusiveness, marks the erotic act of reading, and erotic affirmation cannot overcome the problem that reading involves an encounter with our own separateness, a confrontation with ineluctable otherness, reconfigured as the unreadable. As Gus notes of Whiteread’s muffled monument, the library’s doors are without hinges and, like the reversed and moribund books that line its walls, they are un-openable, forever closed to us: access denied. A cenotaph formed of unreadable books, Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial poses a confrontation with impenetrable separateness. It does not redeem loss and impossibility so much as it makes them visible, marks them, gives them form and coherence. Thus it renders catastrophe almost bearable in order that catastrophic loss cannot be lost on its viewers (and would-be readers), who must stand before it forever deprived of access to its elusive interior, shut out, definitively bereft.

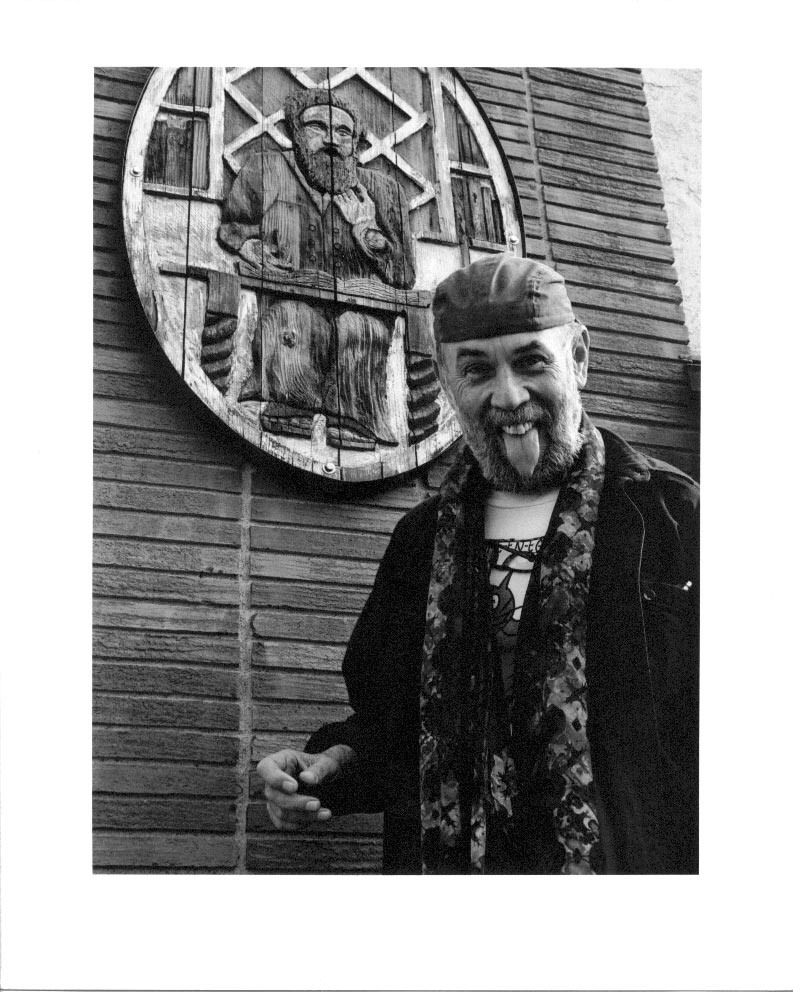

No heavy-metal rock star had a longer tongue, and it served Gus effectively in critical evaluation of movies, ideas, and politicians as well as in his trademark ironic leer. Two extended tongues-out is the evaluation he might likely assign to my account of his “Slipping Across,” where stone, ashes, loss, and absence prove mainly an undertone, a passing (if recurrent) shadow, a whispered reminder that readers and reading form the more problematic side of an unstable equation. The readerly soul never quite manages to slip across, and slipping across always entails slipping back. Writers and writing, by contrast, he affirms in all their unproblematic madness–Orpheus absolved of his fateful backward glance: what writer wouldn’t look back?–and the affirmation has something big to do with generosity and friendship. Many writers, that is, were not so much names on books as people he knew, made it his point to know, and wrapped in the wide, promiscuous, Whitmanesque embrace of his friendship.

Friendship is not a topic Gus wrote about, objectified, but the enabling state or non-native ground from which he wrote, much like his adoptive and beloved New Mexico. It is remarkable how much of his writing, published and unpublished, responded to a request from a friend. Friends knew his value–he was utterly careless about what anyone else might think of him–in fact, he cultivated a style that dared you to misjudge him and simultaneously said he really didn’t give a shit. So friendship was a special condition that nourished writing, much like family. He doubtless knew the classical tradition that defines friends as second selves, an alter ego, sharing complete sympathy in all matters of importance. Cicero’s De Amicitia, however, while full of insight about the importance of friendship, would not survive the contempt in “Slipping Across” for narcissists “whose lips kiss only images of themselves.” Friendships for Gus were, like reading, encounters with otherness. I have met only three people over the course of my life who were gifted in friendship to the degree that, say, Michael Jordan was gifted in basketball. Gus, among them, is unparalleled. Friendship, most often but not always nourished by writing and reading and, yes, by New Mexico, was the medium in which he, simply, lived his life and soared.

Bookseller, publisher, writer: Gus did it all except maybe glue the bindings. Always too with an eye toward his friends, whose work he loved to publish, allowing their words to slip across from breath or mind to print, from writer to reader. A culminating convergence of art, friendship, and otherness finds expression in a small wrapper-bound collection of poems by Robert Creeley, which Gus published in 200 copies on the occasion of Creeley’s February 2000 reading at the Outpost Performance Space, in Albuquerque. The collection is titled, significantly, For Friends. Creeley dedicates each poem to a specific friend, and what unites the collection is moments when friendship mixes with desire and loss. His poem for Allen Ginsberg confronts the bitter moment when loss materializes in the death of a friend. Its title and underlying trope (the loss and re-animation of desire) derive from a short poem in which Walt Whitman describes his dulled response to hearing a lecture by a learned astronomer. Bored, Whitman exits the lecture hall in a “gliding” motion somewhat like slipping out and wanders alone into what he calls the “mystical moist night-air,” looking up at times (“in perfect silence”) at the stars.3 The stars–representing the natural world in its grandeur–reanimate desire lost in a lecture choked with charts and secondhand academic data about stars. The trajectory of Whitman’s poem–the loss and reanimation of desire–resembles fire/desire, banked and almost dead, suddenly blazing back to life. It is a reminder that learning for Gus sparked desire–as in his long riff in “Slipping Across” about Victor Hugo and the history of library architecture–just as, in turn, the desire to write kindled a desire to learn. Like Ezra Pound, Gus had made his own distinctive emancipation pact with Whitman.

Creeley’s elegy for Ginsberg begins in darkness and loss so deep that no star can pierce it. The night’s silence is not perfect or mystical, as for Whitman, but an image of absence lacking even the twitter of birds. Direct contact with the natural world is no longer adequate to offset loss. It offers no consolation, no reanimation of desire. Somehow the poem manages to move through all this negation–disharmony, loss, darkness–to a wholly unsentimental conclusion in which death is not overcome or transcended but rather opposed with the poet’s minimalist tools of rhymed words that ricochet like wild bells. This poetic response to silence and death and supreme unredeemed absence–the loss of a close friend and the death of a truly original poet–builds a threadbare credible affirmation from sounds so primal and unadorned as to evoke the rawest raw material of poetry, but therefore also not negligible, not nothing. In its resistance to the sublime and its starry skies, this raw and minimal not-nothingness, out of which poetry and writing emerge, seems exactly the right affirmation with which to remember Gus Blaisdell, another Creeley friend, and to reaffirm his impossible slipping-across erotics of reading, his desire to write that directed his life, his no-holds-barred embrace of otherness, his genius for friendship:

There is no end

to desire,

to Blake’s fire

to Beckett’s mire,

to any such whatever.

Old friend’s dead

In bed.

Old friends die.

Goodbye!

Fire, mire, desire: drive he sd books / Albuquerque, New Mexico.

DAVID BROWN MORRIS, an emeritus professor of literature at the University of Virginia, is the author of numerous books. His latest Ten Thousand Central Parks; A Climate-Change Parable is out in 2025. https://davidbmorris.com/

Notes: [1] Walt Whitman, “So Long!” in Leaves of Grass (1871-72). The poem is an addition to the Leaves of Grass 1860 first edition. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/

2 Ikkyū, Crow with No Mouth, trans. Stephen Berg, Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2000, p. 54.

3 Walt Whitman, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” in Leaves of Grass (1867). The poem is an addition to the Leaves of Grass 1860 first edition. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/

4 Robert Creeley, “When I heard the learn’d astronomer…” in The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1975-2005, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

SLIPPING ACROSS by Gus Blaisdell

Slipping Across

The visionary poet Ronald Johnson reading from his manuscript “The Imaginary Menagerie” reached a short passage so arresting in its lapidary compression that it deserves to be cut in stone:

who once have sung

snug in the oblong

oblivion

Inscriptions are meant to pull you up short. “Stop, Traveler” is the most common beginning on the inscribed gravestones that bordered ancient Roman highways. Inscriptions in this elegiac genre give speech back to the dead. In Basil Bunting’s poem Briggflatts, a stonemason extols his craft:

Words!

Pens are too light.

Take a chisel to write.

Words, however weighty, bear a curiously unstable relation to stone. In Notre Dame de Paris Victor Hugo has Claude Frollo point at a book as he gestures from his cell window toward the sphinx-like shape of Notre Dame cathedral and utters the phrase: ceci tuera celá: This will kill that.

The chapter that follows this moment is called “Ceci tuera celá” and details the great dialectic of books undoing the Church, a story of freedom increasing through dissemination of the press, of a journey from dark to light, of the spreading literacy producing enlightenment, the testament of stone replaced by the testaments of the printing press.

Hugo’s main source about the history of architecture was the young Neo-Grec architect Henri Labrouste. Later, as if inspired to counter Hugo’s and Frollo’s prophecy, Labrouste built the Bibliothèque Ste-Geneviève. Free at last of the long-standing French obsession with the classical architectural orders, it is a library that reads like a book. Neil Levine, in a magisterial essay on Ste-Geneviève, Labrouste, and Hugo, reads the architectural details in an extended metaphor not only of the book but of the whole process of printing from movable type–from the names on the façade (which may be seen as type locked into chases) to the books of these authors that sit on the shelves directly behind the places where their names appear on the wall. Labrouste built a book of iron and stone that was functional and free, a building dedicated to contemplation and reading, absorption and study. It became a secular version of Hugo’s description of the Temple of Solomon. “It was not merely the binding of it, it was the sacred book itself. From each of its concentric ring-walls, the priests could read the word translated and made manifest to the eye, and could thus follow its transformations from sanctuary to sanctuary until, in its ultimate tabernacle, they could grasp in its most concrete yet still architectural form: the ark. Thus the word was enclosed in the building, but its image was on the envelope like the human figure on the coffin of a mummy.” Labrouste made his library perfectly reflexive and transparent, no difference between the inside and outside.

Hugo set his novel in 1482. Sixty-one years earlier, 12 March 1421, a congregation of Jews burned themselves alive in a synagogue on Judenplatz in Vienna rather than renounce their faith or be murdered by Christians. A plaque in Latin from 1497 commemorates the immolation by referring to the Jews as dogs or curs. Mozart wrote Cosi fan tutte in house 244 overlooking Judenplatz in 1783. On 12 March 1938, Nazi troops entered Vienna, 517 years to the day that the Jews burned themselves. Rachel Whiteread, a young British sculptor, unveiled her remarkable Holocaust memorial on Judenplatz on 25 October 2000, much delayed by politics from its originally scheduled completion date of 9 November 1996, the fifty-eighth anniversary of Kristallnacht.

Before the memorial could be built excavations began on Judenplatz to unearth the original synagogue. The first area dug down to was the bimah, the area where the ark is kept and the desk from which the Torah is read. Whiteread’s memorial measures 12′ x 24′ x 33′ and is a library turned inside out: the spines of the books face into the building. It is a cast made in white cement of the library’s interior. The doors, without hinges or handles, cannot be opened. The library cannot be entered because the imaginary interior, far from being empty, is solid: the presence of absence. “Casting the internal–If Rachel could drink a couple of quarts of plaster or pour resin down her throat, wait until it sets and then peel herself away, I feel she would. She shows us the unseen, the inside out, the parts that go unrecognized,” observed A. M. Homes.

John Baldessari, the California conceptual artist, still has nine and a half boxes of the ashes of his paintings. In 1969, when he realized that he would stop painting, he found a crematorium that would burn his paintings. His motive was to complete the cycle of the chemicals that made up his oil paints by returning them to earth. The original installation at the Jewish Museum in New York was to be an urn containing some of the ashes placed in one wall with a plaque beside it. A major funder of the show said she would withdraw funding if this was done. So Baldessari placed the urn on a pedestal. The urn he chose among the many on offer was in the shape of a book. This was the beginning of conceptual art, the ashes of paintings interred in an urn shaped like a book.

Horace (Odes 3.30.1) claimed he had written poems more enduring (perennior) than bronze and outlasting the pyramids. In “Lector Aere Perennior”–the reader more enduring than bronze–J. V. Cunningham disagrees with Horace. Every poet depends not just on paper or stone or bronze but on readers for his relative immortality. Yet the reader is a problem. What must the reader do if the poet is to have lasting fame? For Cunningham the reader must be:

Some man so deftly mad

His metamorphosed shade,

Leaving the flesh it had,

Breathes on the words they made.

The reader dies (the orgasmic “little death” of the text) that the poet may live again. Transported by the words of the poet, the reader transmigrates his soul and “breathes on the words they make.” His and mine become ours, a more amazing dialectic than turning the book of stone into the book of print.

An epigram by Plato had been a favorite of mine long before Ronald Johnson read to me from his inscription-like “Imaginary Menagerie.” Plato writes that it is said by Socrates to Agathon:

Kissing Agathon, I found

My soul at my lips.

Poor thing!

–It went there, hoping

To slip across.

It is one of the epigrams from The Greek Anthology. Is it somewhere carved in stone? Did each passing Greek read it aloud? Were the lines alternately painted black and red? As the Greek read the epigram aloud his soul too was at his lips, trying to slip across. From his lips to the stone, in a direction opposite that of Socrates whose lips were meeting those welcoming closed lips of Agathon. It is the soul that remembers and speaks in the poem, from within Socrates’ silence.

But though the soul rises to slip across it is a poor thing because it falls back–desire wants to slip across, believes in its heart that metempsychosis is possible, in its delusion a poor thing. This is the giving soul, the one that acknowledges and welcomes the other, not the Freudian narcissists whose lips kiss only images of themselves. And this happens every time we read.

When we read we slip across; we do not fall back. The words they made are like the love we had: the poem read through is like the exhausted beloved, over there, on the other side where we just were. The reader succeeds precisely where Orpheus fails Eurydice. We look back fondly. We behold the lineaments of gratified desire, what men and women in each other do require.

Chris Marker’s film La Jetée (The Jetty, France, 1962) runs 28 minutes and is constructed entirely of stills, except for a single moment of movement.

A brief synopsis of La Jetée will put the complexity of this moment in perspective. The Third World War has taken place; the earth is radioactive, uninhabitable; the victors rule underground over a kingdom of rats; concentration camps flourish one again. The story is of a veteran who survived the war and who carries within him a single image of peacetime: a woman’s face he had seen as a child on the jetty at Orly Airport. Because his imagery is so vivid the camp commandants subject him to experiments: he is injected, travels to the past and eventually to the future. He finds the woman he saw as a child; they fall in love. The moment of movement occurs after they consummate their love.

The woman opens her eyes and blinks three times, looking directly out of the screen. She wakes to look at her lover looking at her. He is not seen by us, but his presence is established by a series of overlapping dissolves in which the sleeping woman changes positions as she sleeps and he watches. The sound over these shots is of bird cries reaching a crescendo–so intense the cries sound like squeals of pain, a mysterious jouissance. (Could this be a Blakean moment? “How do you know but ev’ry Bird that cuts the airy way / Is an immense world of delight, clos’d by your senses five?”)

One of the abiding mysteries of film is that it is a medium of visible absence. In a notebook poem William Blake asked and answered several specific questions, among them the following:

What is it men do in women require?

The lineaments of Gratified Desire.

What is it women do in men require?

The lineaments of Gratified Desire.

To my knowledge, even using what he called his “infernal methods,” Blake never engraved these lapidary lines.

What happens when we read a story, a poem, a book, a building? Are we deftly mad enough to slip over? We love what looks back at us, studying to know everything, knowing the knowledge of love is inexhaustible, and knowing also that such work of the imagination is beyond the reach of even our best words. After having slipped across we return to ourselves, our experience enriched. The reader is like Jacob, blessed by the angel he wrestled. Touched on the thigh before he was released, Jacob was left with a limp. The angel touches us before we are released. If there is a new limp once we return from our struggle, our abandon, our transport, it is the happy fault–the felix culpa–that touches another soul, and both are the better for it. The poet gains his brief immortality; and we return to our mortality exhausted and renewed. Within those moments of movement while we read, and remembering what we read, acknowledging the autonomy and mystery of it, we briefly become the kind of person Henry James wished us to become: one on whom nothing is lost.

Gus Blaisdell 2003

Unpublished. This essay was originally intended for Inscriptions, a deluxe-edition book that was produced by Jack W. Stauffacher in 2003 to commemorate the lapidary inscriptions on the Old Public Library of San Francisco on the occasion of the building’s conversion into a new museum of Asian art. In the end, however, the essay was not used.