From the Editor’s Preface to Gus Blaisdell Collected

Darkness sur- / rounds us

I Know a Man

As I sd to my

friend, because I am

always talking, –John, I

sd which was not his

name, the darkness sur-

rounds us, what

can we do against

it, or else, shall we &

why not, buy a goddamn big car,

drive, he sd, for

christ’s sake, look

out where yr going.

–Robert Creeley

Gus had a special fondness for this poem by his longtime friend Robert Creeley. He took one of its key phrases for the name of one of his publishing imprints, drive he sd books. He also paid homage to Creeley’s poem at the close of the long essay “Buried Silk Exhumed.” There he presented an imaginary anecdote about two of his favorite jazz musicians, Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie, driving (presumably in a “goddamn big car,” top down, shades masking their eyes) along the California coast. “It’s always night,” Gus has Monk remark idly, gazing off to the shimmering afternoon horizon, “because it’s only light when the sun’s up.” To which he has Diz respond, “Monk, you are one deep cat.”

Gus, too, was a deep cat. And while he loved jokes, lively conversation, and tall tales with an intellectual spin, darkness, like Monk’s perpetual night, shadows much of the writing brought together in this book. It is the darkness of human finitude. While we hardly know what truly drives us, it’s a dread of darkness that jump-starts the helter-skelter getaway in Creeley’s poem, apprehension marked with that stammered line break voicing how darkness “sur- / rounds us.” Darkness, in Creeley’s rendering, hovers over us in ominous supremacy and encloses us within its limiting sphere, a nifty turn on Shakespeare’s “our little life is rounded with a sleep” that Gus surely admired.

Like Creeley, Gus brought the instincts of a poet to his philosophical confrontations with darkness. In “Original Face,” an essay about a round, black, tondo-shaped painting by Allan Graham called Moon 2, Gus explores the darkness that precedes consciousness and is our constant companion. He quotes an ancient Zen koan, “Before your mother and father were born, what was your original face?”, to recall for us the darkness of unknowing out of which we have come, and to remind us that we must always look out from behind our own faces, remaining as dark to ourselves as the far side of the moon. Ultimately, self-knowledge, and the relationship of the self to the world, is the central issue addressed in these writings.

“Become the kind of person on whom nothing is lost.” Henry James’s advice to a young writer became a kind of mantra for Gus. It defined for him the task of the critic as well as the poet, and he felt it should be applied to everyday life. You have to observe closely and bring all that you know into your response. As a critic Gus assumes the role of an exemplary responder, showing what it’s like to attend to the work at hand. His essays frequently begin with a kind of preamble (before they take the mind for a walk), in which he tells of his difficulties in trying to come to terms with his topic, the struggle with the evolving hydra-headed implications that would occur to him as he tried to think about it conceptually and get his thoughts down on paper. “Original Face” is the most extraordinary response to a work of art that I have ever encountered. Gus simply presents himself to the work of art, confronts its singularity with his own, and engages with it as a fully embodied consciousness.

“Self-knowledge, no matter how fragmentary and tenuous,” Gus wrote in the 1960s, “is the right kind of knowledge, the dialogue between ourselves and ourselves and between ourselves and the external world.” No matter what the ostensible topic might be—movies, photographs, or the expressive qualities of various works of art, literature, or philosophy that he admired—Gus’s writing revolves around the quest for knowledge of the self and the search for understanding our human placement in the world.

There is a problem, however, at the very heart of the quest for self-knowledge. As Gus once observed about self-consciousness, “It’s interesting that the self, as a prefix, keeps its hyphen, never quite combining with the consciousness it engenders; no, that engenders it.” Consciousness of the self drops a shadow between the self and itself, just as it also intervenes between the self and the world. The black hole of solipsism is poised to suck us in, and the threat of skepticism, with its murky doubts and its despair of certainty (since our physical senses are notoriously untrustworthy and our knowledge of other minds always feels problematic), clouds our outlook on the world “out there.” Darkness “sur-rounds us” indeed.

“How does one get out of the monstrous enclosures of the egocentric self?” Gus asked, writing of his early interest in such philosophers as Descartes and Hume, who agonized over these issues. In a letter to Ross Feld he tells of his early “romance” with the mind/body dualism of Descartes: “I was in search of the idea which engendered the body in the world, as was he [Descartes]. His idea was God, one in which content leads to existence. But that doesn’t work for me. God, for me, is a name for the fruitfulness of our ignorance, a thinking in the dark that pushes us on, and on: a fruitful ignorance.”

So Gus’s God is associated with “a thinking in the dark that pushes us on.” According to Wittgenstein, a key philosopher in Gus’s development, “Thought does not strike us as mysterious while we are thinking, but only when we say, as it were retrospectively: ‘How was that possible?’ How was it possible for thought to deal with the very object itself? We feel as if by means of it we had caught reality in our net.” (Philosophical Investigations, I # 428) But the truth is that neither reality nor the thinking self can be so easily caught. Our only net is language, and our words and our thoughts form substitutes, their referents eerily undetermined. “In the actual use of expressions we make detours, we go by side-roads,” says Wittgenstein (PI, I # 426), “We see the straight highway before us, but of course we cannot use it, because it is permanently closed.” Nevertheless, Gus seems to say, since you’re in the driver’s seat, for christ’s sake, look out where yr going! The line might just be the central message of Gus’s writings, which often, in their pursuit of grace and self-knowledge, take on the sound of admonishing sermons.

A tribute to Robert Creeley on his 70th birthday

Intro

I began secretly studying Japanese in junior high school, military phrase books and character dictionaries, only a couple of years after the war. During the war the woodblock prints and ink-painting scrolls were removed from the walls and I had a fascination with both enemies, playing those roles whenever we played guns and war. The other kids always praised me, “Blaisdell, you really know how to die!” My father, a naval officer, served in the Pacific and again during the Korean war, having his own squadron of destroyers–I loved calling them “tin cans.” He used to send me black, hard rubber models of enemy aircraft, the kind used by spotters for identification, three-dimensional versions of those silhouettes that filled the pages of treasured manuals, and also cast-metal model ships, the kind used in war rooms to plot sea battles. In miniature I had the Japanese fleet and a model of the Nagato, the low-slung battleship whose fate it would unforgettably be to surf up the gigantic stem of the atom bomb tested at Bikini.

My mother divorced my father after Korea. He had been at best intermittent during my childhood, disappearing immediately after Pearl Harbor; returning exhausted and raving only once during the war–they said it was “almost a complete nervous breakdown” (so I guess it was incomplete)–he would not recur in my life until we met when I was twenty-five, a graduate student making myself miserable by trying to find in positivism and mathematical logic something I might call “philosophy.”

As an undergraduate I studied Japanese formally. My hope by this time, unknown during the secret improvisations with phrase books and character dictionaries, always happy in the search there for radicals, was that one day I wanted to read Basho’s Oku no Hosomochi in the original. Dream on! Today, forty years past those upper and lower divisions, over thiry years in our beloved New Mexico–where even conversationally there is little chance of speaking the lingo–a stumblebum among romanji, the kanas and kanji, I still re-read Basho with love and with an always aroused memory of an ambition more youthful than each aboriginal, preasurable, reawakening.

What these flirtations with Japanese gave me, especially the more sophisticated formal one, was a lifelong passion for nikki, the Japanese poetic diary. In my ambition I saw it as a possible literary form, the condition of the prose demanding poetry, and vice-versa; the two in their mutual inspiration creating a third: neither prose nor poetry, and yet both; not something over and above, yet along side and out of, like love consummated, desire gratified, or Eve from Adam’s rib (she is our way of leaving him behind, naming his animals, while we explore the garden and discover the bad girl in ourselves—tempted, seduced and exalted—a real idea of education, in abandon).

2

Nikki: Daybook on Insistence

“The insistence was a part of a reconciliation”

–“The Operation,” from For Love

A couple of weeks ago I started thinking about your 70th birthday, 21 May 1926. That’s a lot of days, twenty-four thousand, nine hundred and twenty, to be exact, like they say. But what exactness is that? Life in days and numbers, the daily and material lost in numerical abstractions.

I know your idiom, can through ear call it to mind like having a poem by heart, line after line in the rhythm of time, unfolding.

But this was to be a gift, one given back for the one you are: it is divine to you to give. You bless. You speak of friends as being good news–yes, gospel, and you evangelical, and by announcing names you touch them. Friendship is not just hanging out, the way circumstances stand around their possibilities, guilty as every bystander, hands in turned-out pockets–this company hand in hand, loafing most invitingly while hearing the soul in the song.

Knowing the idiom, the lingo is always refreshed by yet another reading; in the mother tongue less chance of being a stumblebum though head over heels in love with the sound of it. I read For Love at a sitting on a hot afternoon. I began noting favorite words, phrases, diction, thinking to assemble them in a bouquet, like The Greek Anthology; but in no time I was writing down titles, acknowledging the unparaphrasable integrity of the poems, page after page, poem upon poem, my own selected bulking up. Would it be the same on another reading? I trust not: it would accumulate like a reef until all I had in hand was the book itself.

A note: insisted: to be of use / measured sense / puts hands and candles in / minds caressed and light / let it. What need of light when love guides hands.

Another note: wicker basket / woven, like a text, to fit what it contains / is never more than an extension of content. / Three of them brought wisdom over the highest mountains in the world: Tripitaka: one of discipline, the second of wisdom, and the third contained metaphysics. The baskets disappear beyond imagination and what remains? The poems they are / as they are.

3

Insistence is urgent, pressing, and it lasts, compelling attention. In the interview the other guy said he thought Lacy was a wonderful original. “I do too,” you said, “He’s tough. He stays put.”

There’s the idiomatic insistent rhythm that I hear repeatedly in Luther’s “Hier stehe ich, ich kann nichts anders.”

That Hardy older man of Echoes’ “First Rain,” momently Catullian in “Self Portrait,” finding the composure of “Stone” (Aquinas: “Stones point toward their homes”) and the winning abandon of “Echoes”: “Say yes to the wasted / empty places. The guesses / Were as good as any.”

Sometimes when I imagine our New Mexico I see the volcanic and flat horizon of the West Mesa, rearing eternally its arid tsunami above the Rio Grande, and as if a child dripped from its hand the sand to build its castle from the hard inshore, I see me say, “Creeley is Giacometti to this place.”

On my fiftieth birthday I was in Cambridge for a year. It chanced that it was also the 350th anniversary of the Blaisdells’ arrival in New England in Richard Mather’s company aboard the Angel Gabriel, tossed ashore over her masts and cracking like a nut on that rocky coast. Not a soul was lost, amazingly, and all those years later the Invitation to the anniversary bid us come and drink in water a toast to our common ancestor–could that really have been the syntax! For my birthday my girlfriend went to the Concord Cemetary, climbed the hill and took a snapshot of Thoreau’s headstone: HENRY is all its granitic slate said.

The locomotive dark still drives toward dawn. Henry said we had constructed an engine worthy of ourselves. He called it Atropos, a fate, one that doesn’t turn aside but keeps going. He said he would like to be a track repairer somewhere in the orbit of the earth.

I spent years asking friends, including you, who it was had said, “a tiny piece of steel, properly placed,” and you all said, “Lew Welch.” Nobody could find it. Eventually it turned up in one of Jonathan Williams’ quote books: it was yours. It had that hard Dickinsonian ring to it. I imagined the train un-derailed, running over the tiny piece of steel, shooting it off the rail, into a poet’s hand, leaving it sharp as a burin–and the poet keys the train, from the locomotive with its slashing Mars-light to the red-eyed disappearance of the caboose.

5/17: I was flipping through Echoes in search of a poem when my eye was caught by a poem inside that you’d inscribed but I had not previously seen: “Pure,” about how it can be an inspiration–indeed, a drawing in of breath–even when the toilet backs up through the bathtub drain while one is showering.

4

That night I crossed over the bridge of dreams, as the nikki say. My mother’s long black hair came out of the drain hole in the tub and lashed itself around my tattooed ankle. I was not terrified, and instead of waking from my nightmare stayed asleep, walked in sleep as I had as a child, down the hall, into the living room, and woke with a book in my hand. I knew where to look even while still dreaming: Basho’s Record of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton.

The great poet returns to his birthplace and is shocked at how everybody has aged. One of his brothers likens him to Urashima, whose hair turned white on opening a miracle box. The brother hands such a box to Basho. It contains his umbilical cord and a lock of his mother’s hair: “Should I hold it in my hand / It would melt in my burning tears / Autumnal frost.”

I know a man whose years of blessings I am honored to return on his birthday. I am so glad he is talking all the time, talking back the surrounding darkness, putting in the candles where they need to be, forgiving and lightening my own once cyclopean dark with his friendship and his poetry.

1996 / 2001 (?)

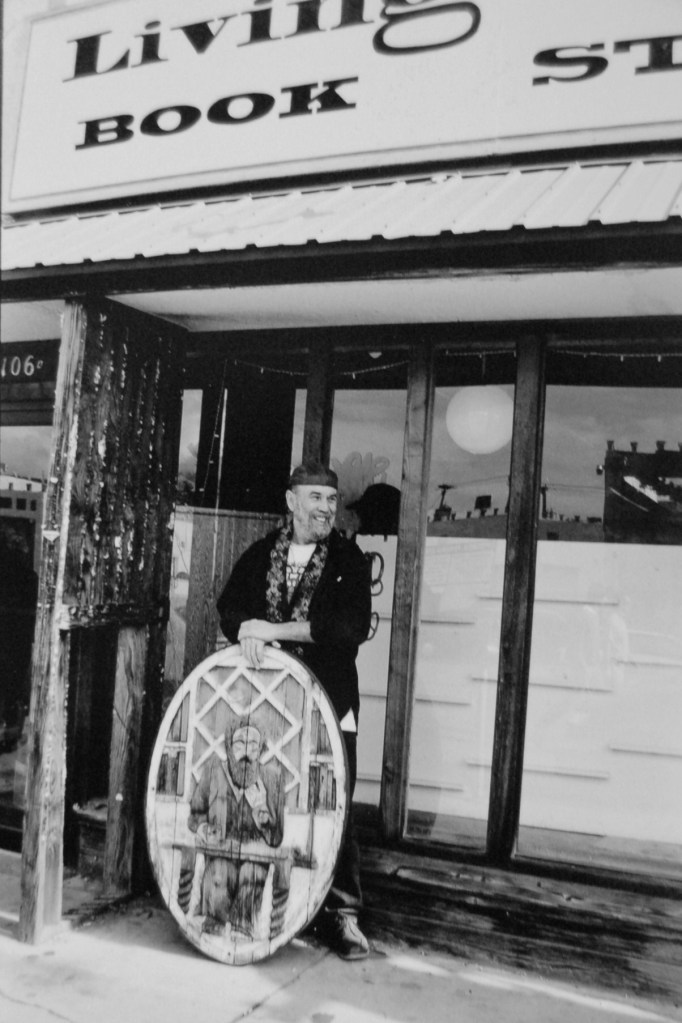

Undated and unpublished computer-file manuscript. While it was almost certainly composed in May 1996, on the occasion of Robert Creeley’s 70th birthday,this piece was probably revised in the fall of 2001 when Gus submitted it for consideration for possible inclusion in the UNM Press collection, In Company: an Anthology of New Mexico Poets after 1960. It was not used in the anthology, however. In correspondence Gus indicated that he considered this text to be a poem in prose.