Passion Misfits Us All: Wim Wender’s Paris, Texas

It is around such ordinary things as a joke, a home movie and a dramatic realization of jealousy that Paris, Texas revolves.

Four years before the events we are shown began, Travis Clay Henderson Jr.’s marriage exploded. Jane, his wife, fled with their son, Hunter, pausing only long enough to leave him with Travis’s brother and sister-in-law, Walt and Anne. Since that time Walt and Anne have come to love Hunter as if he were their own. Yet they have been living under the cloud of a mystery. They do not know what happened four years ago. Nor do they know the whereabouts of Travis or Jane. All they know is that their disappearance four years ago accidentally turned a childless couple in a troubled marriage into a happy family.

Paris, Texas begins with Travis reappearing somewhere in Texas as suddenly and inexplicably as he originally disappeared. Walt goes to get him and the two of them drive back to Los Angeles, where Anne apprehensively awaits their return, her household once again as threatened with disruptive change as it was when the original, still unexplained events occurred.

“Paris,” is the word Travis chooses to break his silence on the drive back. Walt, taking him to mean the capital of France, says that he’s never been there. Travis asks if they can go there now and Walt replies lightly that it is a little out of the way. Travis, who is in the back seat, looks down at a Mexican map of Texas. On it, “Paris” is penciled in; he chuckles. Walt reminds him that Anne is French but not Parisian.

In their next exchange around “Paris,” Travis produces a snapshot of Paris. Walt asks to see it and is surprised when he sees a vacant lot, some drooping strands of barbed wire, a realtor’s sign, and a discarded Coke bottle in the foreground. Walt registers his disbelief, “Looks like Texas to me.” Travis chuckles, says that it is. “Paris, Texas?” Walt asks in incredulous tones.

Does Walt recall their mother’s maiden name? Sequín, Mary Sequín. Yes, her father was Mexican.

Later, as they wait at an intersection, Travis remembers why he bought the piece of wasteland in Paris, Texas. Their mother told him that she and their father first made love in Paris, Texas; and he has always believed that he was conceived there. He bought the land in the hopes of one day settling there with Jane and Hunter.

These concerns around Paris, Texas conclude as Walt and Travis arrive in Los Angeles. Travis recalls their father’s joke. The old man would introduce their mother as being from Paris. He would pause, letting the natural assumption settle in; and then he would add, “Texas,” and he would “laugh real hard.”

I have drawn out in order this sequence of seeming non sequiturs–really incongruous premises–because their father’s joke broods over the whole movie, providing it with a loose dramatic structure. Told at their mother’s expense, one exposing her for what she is (and isn’t), as well as showing the teller for what he is (and isn’t), the joke registers the father’s disappointments (he still dreams of “fancy women”) and resentment (disappointment become revenge) at the real circumstances of his life. It has shaped to a large extent the lives that both Travis and Walt are living. Without meaning to, and not really knowing that he was doing it, on the drive back, as he recovered his memory by working through his set of incongruous premises, Travis has cast Walt in the same role that their father cast their mother. Travis Sr.’s joke is a dream, one condensed by disappointment in a once-happy love into a mocking, humiliating routine but extended by resentment, disgust and contempt into a scene as dramatic as any one-act play. His joke curses life and, by humiliating his wife, denies love.

Travis is no literary romantic longing for origins. He is both simpler and more challenging. He wishes to live where he was conceived, not where he was born. However obscure his reasons might seem for buying his barren piece of land, and comic and ridiculous if the snapshot is taken literally, what the snapshot means to him is his one chance for happiness, something he was probably raised believing was his constitutional right as an American. Travis is poor but he has loved passionately. Travis is poor but he has been destroyed by alcohol, his marriage by jealousy. Travis is poor but has a right to happiness. He would live where his parents were lovers, happy and passionate, however briefly. He was the unhappy accident, the first unwanted child, that ruined their passions–at least his father’s for his mother. Paris, Texas is where happiness expressed itself and it holds out a possibility of well-being before rancor and disappointment, frustration and meanness and bitter hardship. His chance would be there, to live as husband, father and lover, three tasks at which he has so far failed even more spectacularly than did his own father. (Of less importance but some interest is the mythic implication that Travis was conceived in love, out of wedlock, and that he is of mixed ancestry, confirming as natural those seemingly outcast, marginal, outlaw, and misfit aspects of his personality.)

The singly most important dramatic event that occurs during Travis’s sojourn in Los Angeles is Walt’s screening a Super-8 home movie he made when they visited Travis and Jane and Hunter about four years ago down in Texas. No, Travis says just before the screening, he doesn’t remember the visit. Walt projects the film. Anne and Travis sit together while Hunter, claiming to be bored because he has seen it all before, watches from behind the aquarium: what he watches with more interest than the film are the reactions of the man he hardly remembers but who, he is told, is his father.

The Super-8 is projected flush with our screen. We see what all the others do. But when the lights come up in the Henderson living room, and as Hunter goes to Travis’s side, we are aware that although we have seen what Travis has seen we do not know what he knows. Moved deeply, as Hunter sees, he does not tell what he knows but keeps silent. The sight of Jane shocked him. He gasped, and Hunter has watched a range of expressions play across his father’s face. Hunter knows that Travis still loves Jane. He tacitly acknowledges Travis as his father. What the home movie shows is happier times; what it does is bring Travis further into the present, restoring more feelings and memories, providing him with images to oppose to those that haunt the darkness and fissures and gaps that are presently himself. Walt’s projection realigns him. He is acquiring a purpose for his love. What he lacks is a direction.

Coming out of the desert, burned out and nearly amnesiac, Travis possessed his Mexican map, the photomat strip of the three of them when they were still a family, and the realtor’s snapshot of his mail-order groom’s dream of origins. If we called the home movie “Somewhere near Paris, Texas,” and thought of the photomat strip as footage and the snapshot as a location shot–production stills–then the home movie absorbs and animates these fragments, making them more comprehensive. In watching, Travis is reanimated, going from a burnt-out case to a waking, enlivened, quickening soul, one accumulating slowly, through imagery, a vividly illustrated purpose. The next night Travis guides Hunter through the family album, Hunter telling him that he can feel the difference between the dead and the living who only happen to be absent, an ability that has told him all along that his mother and father were alive. The following day when Anne tells Travis about Jane’s monthly deposits for Hunter–that they are made in Texas, at a particular bank, and usually on the fifth of each month–her hope of dislodging Travis from her picture of her family gives his purpose a direction. He is ready to begin his search for his lost love.

Ideas of imagery are central to this movie. Walt and Anne are in the business of making enormous billboards, the kind you see along freeways. Walt shot, directed, and edited the home movie. Yet Walt and Anne, image makers, often confuse images with their originals. Walt does this when Travis is talking about the land at Paris, Texas and Walt mistakenly thinks he’s talking about the snapshot of it. Anne is corrected by Hunter when she says that his mother, Jane, is up there in the home movie. That was not his mother, Hunter says, only her image. She is a princess and a star in a “galaxy far, far away.” Hunter can tell images from their originals. Travis can’t, but his is a problem different from Walt’s and Anne’s. His images, of Jane and of his father’s joke, are obsessive. He is addicted to them and enslaved by them. He must be disabused. Jane, too, as it turns out: she has a wrong idea about the fundamental relation between the human image and its original. Images in Paris, Texas are not phantoms or phenomena. They are the flesh of ideas, full of impacted thoughts and feelings. The characters are entangled with them and they struggle, often agonizingly, for perspective, release, or just a little slack, some loosening of their fierce grip.

Twice while watching it I began to see the signal importance of the home movie. The scene at the end of the film when Jane turns with Hunter around her waist sent me immediately back to her dervish on the beach as she spins away, alone, from her relatives, her arms raised and her wrists propelling her with their strange flutterings. But I had also been returned to it when Jane beat against the one-way glass at the Keyhole Club, trying to get through it to Travis. Here too it was some special quality to her wrists and hands that took me back to that telling, haunting image of her spinning and turning, alone on the hard inshore sand. Did she release pain? Did she invoke ecstasy? Walt’s introduction to the screening and Travis’s later confession of their lives together make us realize that the Super-8 was shot at the end of their marriage. In the movie of happier times, Travis and Jane were keeping up appearances for the sake of visiting relatives.

They were acting. That may have been what made Jane’s spinning away so startling and unforgettable, its spontaneity and desperation beyond any role. But the rest of the home movie had to be their trying to play successfully at being a happy family, of fulfilling, even relying upon, the conventions of a home movie made by visiting relatives. What the camera forces on them they comply with, and though the times are the worst of times, the most nightmarish in their marriage, what we see is what Travis is knowingly silent about: what we see are happy times. He knows they were not. He does not tell us why. We learn when he confesses to Jane.

Characters in this film feel screened from each other, not just literally and dramatically, like Jane and Travis at the Keyhole Club or as Travis is from himself as he watches the home movie, but as though internally isolated from each other and, worse still, isolated from themselves within themselves, as if the self itself is that which falls within itself, backsliding forever in darkness–as though there were screens and barriers upon which they project, not knowing whether they see ideas or things, realities within or without, of their own makings or somebody else’s. These ideas of themselves and of each other are the screens they must remove. The screens within, like the one we watch in a screening, are continuously full of projections, one image simultaneously replacing the other. The feeling is one of seamlessness, from which the self recoils. Falling away feels like loosening, if not breaking, its hold. Being enclosed by ideas, locked into isolation booths of the self, subjugated by ideas, or thinking one is free while all the time complying with the needs of others, all these are ideas fleshed out in the sequences at the Keyhole Club, the point at which Paris, Texas begins ending.

A good deal of the home movie, a documentary, is fictional. How much we will not know until the feature containing it ends. It is at least as fictional as the feature containing it, yet the home movie feels documentary. Paris, Texas suspends these questions within one another and brilliantly throughout the remainder of the movie exploits the interplay of the questions of the amount of fiction in documentaries together with the necessity of reality in features.

The containing feature ends differently from the contained movie. Travis and Hunter do not dance on a dock. Instead, with his legs wrapped so tightly around her waist it feels like he would enter her womb again, Jane turns joyously with her son, a movement similar to her earlier spinning in the home movie. There, unfulfilled and empty and violated, she turns alone in the universe; here, they turn together, a new constellation in a room high, high in the sky, free from the prying eyes and benighted enclosures of the Keyhole Club. This reality is a scene Travis produces. He pauses beside the Ranchero. He looks up at the small lighted square where two people he loves are being reunited. He can’t see what is happening in that room. Then we understand that he has no need to see. He knows without looking what is transpiring up there. Walt works on Travis, projecting and screening a reality, some of which is fictional, mere appearances. Travis, greatly recovered by his brother’s and his son’s help, now creates a reality he knows and needn’t see. His confession of their lives together to Jane has freed all three of them for each other.

The last third of Paris, Texas centers around an erotic den, a peepshow called The Keyhole Club, where Travis finds Jane. It falls rather conveniently into four parts. In the first, Travis is instructed in the mechanics of the peepshow and has his first anonymous interview with Jane. Next, disgusted and revolted by what Jane has become and by his own guilt, and not knowing how or what to tell his son, Travis and Hunter pull off the road in a small town; Travis spends some time drinking and thinking about all that has happened so far. The third section is his second interview with Jane, when Travis narratively confesses their lives together. The final part sees Jane and Hunter reunited and the film ends as Travis drives away.

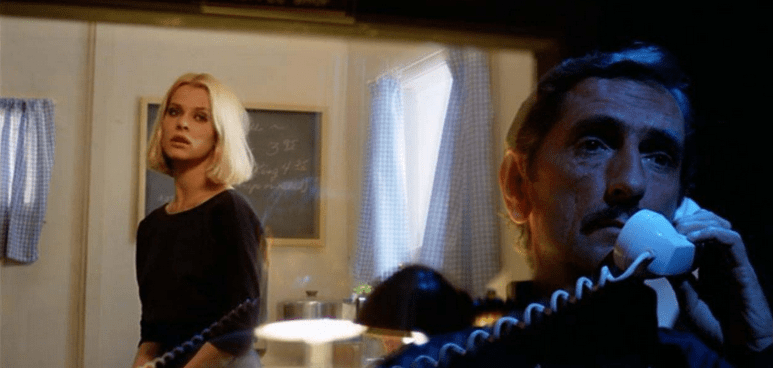

Downstairs in the Keyhole Club there are twenty-four booths. The caller enters. Inside he discovers a telephone and what appears to be a mirror. When the light is turned on in the booth opposite, however, the mirror becomes a one-way glass, the caller seeing the subject of his desires while she sees only her own reflection, the client screened by her image. The booths remind us of confessionals, lavatory stalls, phone booths, and photomats. Most of all they bring to mind those rooms for visitors in prison or observation rooms in asylums, places where interrogations are watched unobserved or aberrant, violent behavior is safely studied, the subject unaware of the unseen watchers. Distance and the ordinary scenes on the subject side (poolside, hotel room, coffee shop) are erotically debased, erotically satisfying. Caller and client have absolute privacy. They are captives of the caller’s ideas. The booths mock privacy’s needs.

When Travis and Hunter pause in the small-town bar Hunter is the one who guides his self-pitying, dangerously sentimental, jealous and outraged father back to his unfinished business with Jane. Travis stands at the bar, drinking and looking at his snapshot dream of origins and happiness. He tells his dream to Hunter. Hunter sneers at the idea. The snapshot just shows a lot of dirt. He also rejects his father’s drinking. The stuff smells awful, and Hunter goes to the car to wait. Travis flips away his snapshot and staggers from the bar. Hunter guides his drunken father to a couch in a laundromat and sits at his head listening to Travis blurt out and reject a garbled version of his father’s joke. No matter how drunk he may be Travis is now aware of the cruelty in his father’s treatment of his mother and of the revenge his idea of fancy women enfolds. The next morning Travis has drunkenly slept off his father’s joke, his father’s idea of fancy women, and his own dreams of a happy ending–living in Paris, Texas, reunited with Jane and Hunter. As Hunter seems instinctively to know, Travis is now ready to return to Jane and conclude whatever it was they started. His dream of origins is either still on the barroom floor or swept out with the morning trash. Travis has no further need of that version of it. He knows his father for what he was, his mother for her long-suffering goodness, perhaps even the beauty of her plainness, her having escaped the fate of so many fancy women; and he also knows himself for what he has been and presently is. The task he faces is far from easy. He must persuade Jane to leave the erotically-charged confines of the Keyhole Club and return to the unexciting rooms of ordinary experience. Her reward, and the stake, is Hunter. Furthermore, Travis must do this without force, the taciturn man forced to persuasive words.

Bathed in blue light in the Keyhole confession booth, he begins the story of “these people.” They had a passionate, adventurous, transforming period. They were together day and night. Then the projections of his needs, his jealous, sentimental, cruel, possessive, violent, addictive love, screened them from one another. His drinking and his jealousy turned their trailer home into an inferno. Into this a child was born. But the enclosure of his vision only narrowed the confines of them all. She began fulfilling his dream of unfaithfulness by sporadically running away. He tied a bell to her ankle. One night, after she had escaped anyway, he tied her with his belt to the stove. He woke in flames. She had fled with the child. The suggestion is that she set him afire. It is also that his jealous imagination, his drinking and his insatiable addiction to her spontaneously combusted. Jane recognizes their story.

Jane is at the Keyhole Club because she refused the fate of Travis’s mother. She would not be the victim of a man’s jealousy, his rages and his drinking. Nor would she be held captive by him because of an unwanted child. He treated her like a cow, tying a bell to her ankle, and like a slave, strapping her to the stove with his belt after one escape attempt. She is safe from all that here. She can’t see them. Only their voices come to her. She is out of reach. They can’t touch her. All she has to do is put on a little act, remove her clothes, comply with their fantasies. She looks at her reflection, seeing what she does, playing at it and acting through the reflection of herself that screens her from them. She has escaped not only the trailer but also a male dream of dominance, possession, and ownership; she has escaped the brutal, murderous consequences of passionate love’s collapse. She believes she is beyond Travis’s childhood home, her hideous revision of that in their life together in the trailer. Where is she really? To what has she subjected herself? For her body’s safety she has traded her soul’s exposure. Jane denies her body and yet continues to use it. She believes it covers her like an actor’s mask. After the bypassed body there is only the nakedness of the abandoned soul. Jane would deny that she is a prostitute. Travis tried to badger her into admitting just that when he suggested that she dated customers after hours. She just lets them look. She listens, does what they want, provokes them a little, like offering to take her clothes off without being asked. She is as far from their reach as the original of a photograph is. Behind the one-way glass she might as well be underwater or in some other world, the star and the princess of their desires. She rules them, she thinks. But without knowing it her life at the Keyhole Club is the erotic debasement of Hunter’s dream of her. Here, she is only up there, in a movie, an image in her own mind as well as those of her clients. In these booths all calls are long distance, the distance itself the obstacle, as charged with need as the line with electricity, and all the callers and all their calls are obscene. Whether she likes receiving such calls, such attentions, or not, it is the work she does. She dissociates herself as best she can from all this, slipping between her reflection and her feelings, watching herself project herself. But the slipping becomes a fall, something Travis fears more than heights: falling. (He confessed this fear to Walt while watching the construction of a billboard and earlier he had refused to fly on an airliner.) The self for Jane is what falls through the cracks of itself, away from itself, until it finds the final corner in which to cower. She becomes numb, dull, professional, less immediate than a soul needs to be and, her privacy assaulted, is once again held captive. She is on the other side of the glass.

Her discourse with herself must be no less indirect than her conversations with her callers. She is wedged in herself in exchange for being impenetrable, unimpregnable, and inviolable. Her final defense against all the anonymous callers is to give them all Travis’s voice. So it is always Travis who is in her soul. The Keyhole Club is a benighted, more abstract version of life in the trailer. Jane, without knowing it, has allowed the trailer to be redecorated. She has made room for herself inside Travis’s jealousy. She still loves him. She loves Hunter. The life she presently lives denies the one she previously lived. The cost is that now her soul is prostituted. Travis has made her unfaithful to infidelity, and the Keyhole embodies his worst fears and dreams come true. (Jealousy, Iago tells Othello, is a green-eyed monster that mocks the meat it feeds on.) By staying away in his drunkenness Travis provided the very conditions he dreaded, ones in which Jane could be unfaithful. In the Keyhole Club the conditions are institutionalized. Her soul is unendingly unfaithful, every caller making Travis’s dreadful dreams nightmarishly true. Within the institutional interpretation that is the Keyhole Club, Jane has discovered an accommodation that shoves her ever deeper into the most hidden parts of a wasting soul but at the same time sends her back, making room for her in Travis’s jealousy, a place where she cannot be hit. She is a celibate whore. She and Travis are still in the trailer. His job is to free them from it and to free them from, and for, each other. It is on hearing the word “trailer” that she knows her caller is Travis.

He confesses their life to her with his back turned. He knows his past effects and he also knows that what he is doing is painful and violent. Confession is only good for the soul in harrowing it. When he finishes his story of their life together, turns and listens to her feelings, then is Travis free for the moment of the past. He is restored not to a whole life but to a clear understanding of what he has been and of how it is that which has brought him here. He sees that jealousy perverts love. It has prostituted the woman he idolizes still. It makes of the plainly beautiful the merely fancy, of the revelations of the body only debased exposures. Despair is so willing, luxurious, obliging and compliant, as sure of itself and its reign as it is of desire pursuing its ends and achieving them in the face of, even because of, obstacles. Jane long ago passed beyond the confines of the Keyhole Club. Dwelling in an unimaginative, institutional literalization of desire uncomplicated by flesh and passion satisfied without feeling, she lives abstractly in the very metaphysics that grounded the trailer and underscored the father’s joke. She is infernal, her clients incubuses to her succubus. The fantasies she lives are not her own. Even Travis’s voice, which she regards as her last resort, must bedevil her.

It takes almost all of these to make the scene work in the hotel room when Jane and Hunter are reunited. That is a scene which must deny all the metaphysics of childhood home, trailer, and peepshow. It is high in the sky, private and ordinary. No eyes pry, no voices make demands. There is in that room all the room in the world, a mother’s love for her son and a child’s response. Travis has no need to see what he already knows. He drives off, action replacing the undertow of passion. They are together. Now he has himself to work on, beginning all over again. Hunter and Jane, and Paris, Texas itself overcome screening at this point. The ordinary, seldom documented, transcends the eroticized hotel-room set in the Keyhole Club by becoming an ordinary hotel room in the Meridian Hotel. Precarious is the alternating balance between the erotic, the ordinary, and the ordinary under the exploitation of the erotic. Jane and Hunter are far, far away from the impacted visions of love that preceded this last scene. The thought seems to be that passion suffers itself not to be transformed. In its struggle to maintain itself, something it knows it will fail to do, passion represents the ordinary as boring and tedious. For in a mother’s love for her son passion (no smarter than any other human being) seems its own demise. It resists change, conservative as such suffering always is. It encloses the self, enchants the senses, and then collapses utterly when faced with transformation.

This last scene in Paris, Texas suggests that the ideal it showed in the home movie might just be attained. If reality is what we aim at documenting, then drama or fiction might be our ways of achieving it, things outside and beyond ourselves that are ideals, not just ideas, and which if need be we can reach. Once reached we may have to disabuse ourselves once again. Can passionate love be housed and domesticated? Passion is always there to knock us over. As Paris, Texas shows it can happen to anyone. Passion is as desired as it is dreaded, and we could sort this all out could we strike the proper balance between passion, love, and jealousy. Who lives that deeply in the present of the world? My guess is that Travis represents a beginning, one that acknowledges the outlaw nature of passion. He drives toward it in the night.

Gus Blaisdell

Paris, Texas, a Twentieth Century Fox TLC Films release; directed by Wim Wenders; written by Sam Shepard; starring Harry Dean Stanton, Nastassja Kinski, Dean Stockwell, Aurore Clement, and Hunter Carson.

1985

From Artspace, vol. 9, no. 3, Summer 1985.

Showing at the Center for Contemporary Art in Santa, Fe NM Through September 19th, 2024

Presented from a breathtaking new 4K Restoration! New German Cinema pioneer Wim Wenders (Wings of Desire) brings his keen eye for landscape to the American Southwest in Paris, Texas, a profoundly moving character study written by Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Sam Shepard. Paris, Texas follows the mysterious, nearly mute drifter Travis (a magnificent Harry Dean Stanton, whose face is a landscape all its own) as he tries to reconnect with his young son, living with his brother (Dean Stockwell) in Los Angeles, and his missing wife (Nastassja Kinski). From this simple setup, Wenders and Shepard produce a powerful statement on codes of masculinity and the myth of the American family, as well as an exquisite visual exploration of a vast, crumbling world of canyons and neon.

https://ccasantafe.org/https://ccasantafe.org/event/paris-texas/